Women in all kinds of areas experience domestic abuse. They may seek help and support informally – or from services.

Many stay put – and need services and authorities to do their job to tackle the perpetrator: to hold him to account.

Others move – but remain local – seeking the safety from relocation, but keeping as close as they can to key – and familiar – support and work, school and other services.

But thousands of women and children have to go elsewhere – as the only way to become safe and start again with their lives.

Often women have little choice about where they can go – they might simply want the most unlikely place: a place where the perpetrator won’t think to look. And, if they need to access services – such as refuges – they have to go wherever there is a vacancy.

But it is striking that women tend to go to the same kind of place[1]. If they can’t find a refuge place in a similar type of area, they may be able to return to that type of area further on down their journey. So women from urban areas tend to stay in urban areas; and rural women tend to stay in the kind of area they are familiar with.

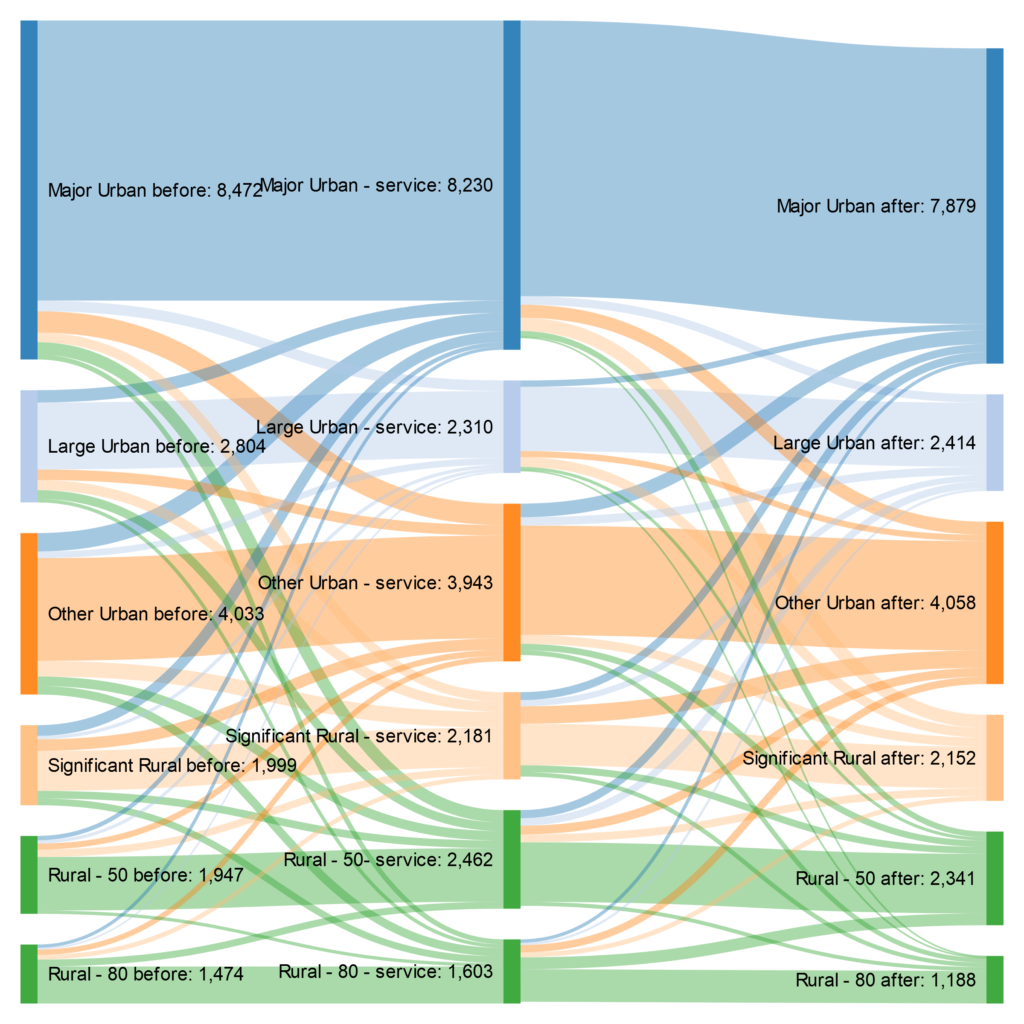

Analysis of different stages of nearly 20,000 woman-journeys to access services, and afterwards, shows the flows from the six Rural-Urban categories in England[2].

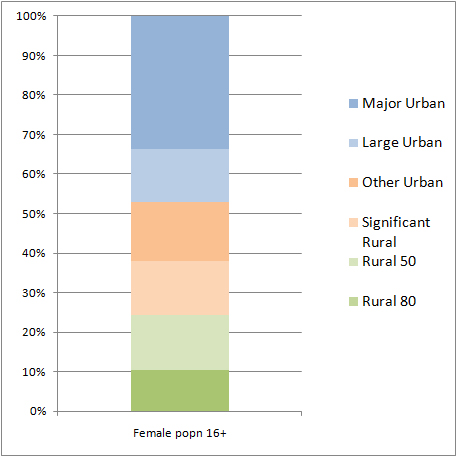

It is clear that the majority of women and children are from Major Urban areas – because this is also by far the largest category of local authority in England for the whole population – as the graph below shows[1].

The flow diagram also shows significant patterns – the kinds of places where women access services; and where they go afterwards.

Their domestic violence journeys clearly tend to be to the same kind of area, so that even if rural women have to go to a more urban area to find service support, they can return to a rural area after the service. And the most Urban areas are actually net leaving overall (from 8,472 women to 7,879 women; and 2,804 to 2,414); whereas the most Rural areas show a slight net arriving overall (from 1,947 to 2,341 and from 1,474 to 1,188).

It makes sense – women are trying to escape the violence, but they want to stay in their kind of town: the kind of place where they and their children can start again after abuse.

[1] ONS. 2014. Mid-2011 Population Estimates: Single Year of Age and Sex for Local Authorities in England and Wales; Estimated Resident Population; Revised in Light of the 2011 Census. London: Office for National Statistics.

[1] Bowstead, Janet C. 2015. “Forced Migration in the United Kingdom: Women’s Journeys to Escape Domestic Violence.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 40 (3): 307–320. doi:10.1111/tran.12085.

[2] Analysis by Janet C. Bowstead using data fromDepartment for Communities and Local Government and University of St Andrews, Centre for Housing Research (2012) Supporting People Client Records and Outcomes, 2003/04-2010/11: Special Licence Access [computer file]. Colchester, Essex, UK Data Archive [distributor]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-7020-1