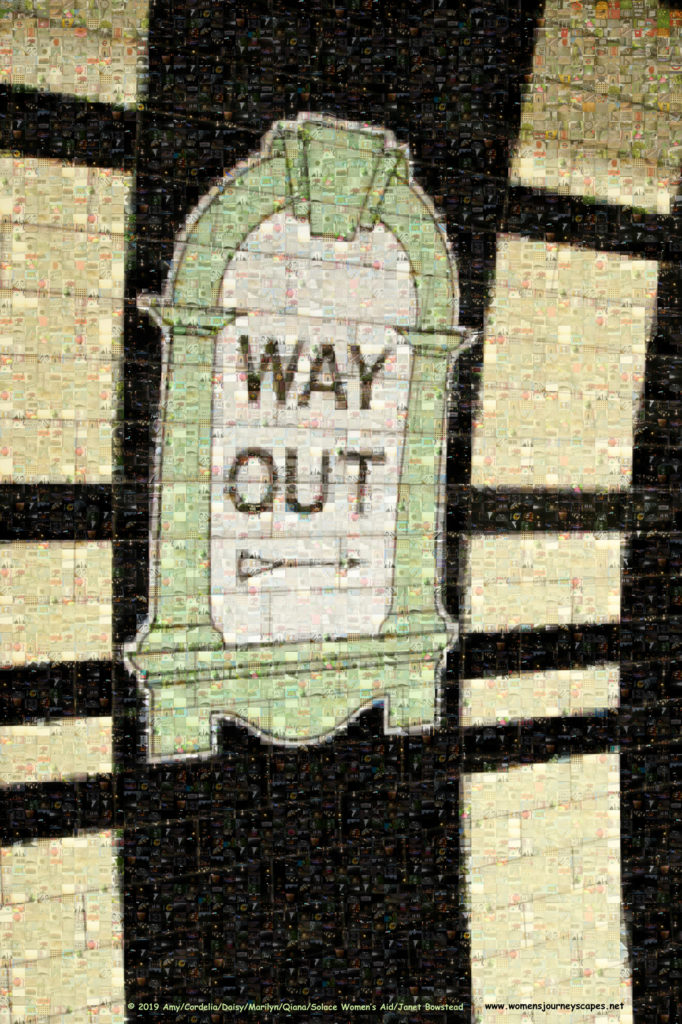

Women on the move due to domestic abuse are often hiding. They shouldn’t have to, of course…

But if not enough is happening to tackle the perpetrator, then women and children frequently have to move away – to try and keep safe. If the authorities will not prevent the abuser threatening her – and if he won’t change – then women uproot themselves and their children and try to disappear.

They may have to keep hidden for months, for years, forever – breaking contact with work, school, friends, family…

And hiding from the perpetrator also keeps them hidden from other aspects of ordinary life. It also means that they slip between the cracks of all kinds of administrative processes – falling off waiting lists, missing crucial appointments, losing their eligibility for services.

They are also uncounted in another way. All the social surveys in the UK sample the settled population – using the Royal Mail’s Postcode Address File – and so this excludes people in insecure, shared, and communal accommodation. Women on the move due to domestic violence may be in temporary accommodation for years – they may never get back to properly settled accommodation.

So the key surveys that are relied upon for prevalence of domestic violence and abuse (the Crime Surveys in England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) systematically exclude anyone on the move or in unsettled accommodation. They exclude the people most acutely affected by the domestic abuse that they claim to count.

There was discussion of the problem at the RadStats conference in London on Saturday; and there is some wider acknowledgement – the Inclusive Data Taskforce (IDTF) reported in 2021 on the issue, and the Office for National Statistics has recently published research with 40 women on temporary accommodation due to domestic abuse.

But this doesn’t fill the gaps – there’s nothing more substantial to address the chronically uncounted; and the implications of them being missing from statistics. The supposed prevalence of domestic abuse – measured by the Crime Surveys – is widely reported; but it is barely acknowledged that the figure is potentially badly skewed by the missing women on the move.

And the missing are predominantly women – not only are women more likely to experience domestic violence and abuse, but when men experience domestic violence and abuse they are less likely to relocate and therefore exit the settled population sampling frame. So the prevalence for men and women are differentially skewed – meaning that the figures just cannot be relied upon.

So – from the assumption of only surveying the settled population, comes distorted statistics and significant exclusions.

And it matters – whenever the supposed prevalence of domestic violence and abuse from Crime Surveys is used to assess need, or make decisions about whether to provide services – and services for whom – the basis is flawed… and the decisions are flawed. And the message seems to be that the uncounted – women and children on the move due to domestic abuse – just don’t count…