Government often talks about evidence-based policy.

– and calls for further evidence and research from those who argue that policies or laws need to be changed.

But part of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 is a classic example of Government ignoring existing evidence – evidence that was presented to them in the consultation on developing the Act – and setting law and policy up to fail.

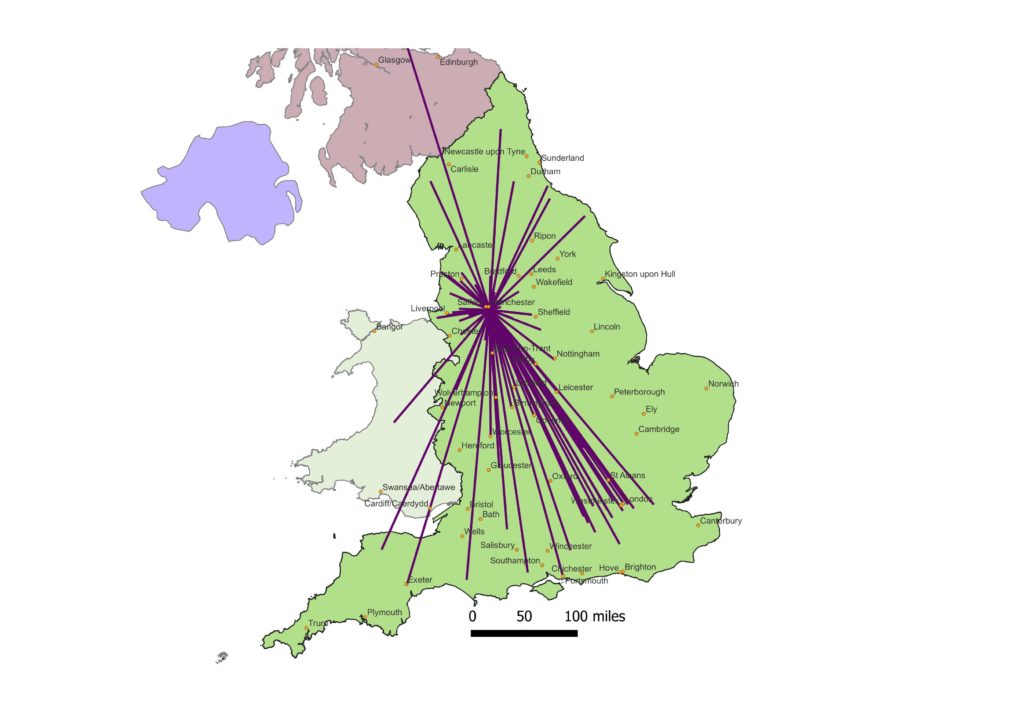

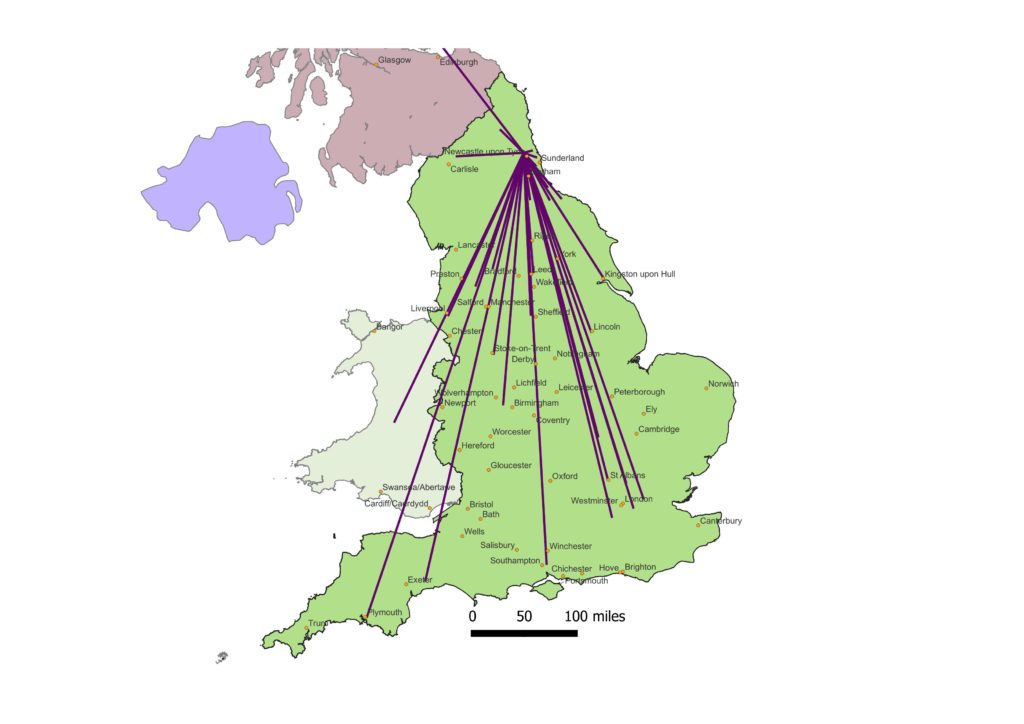

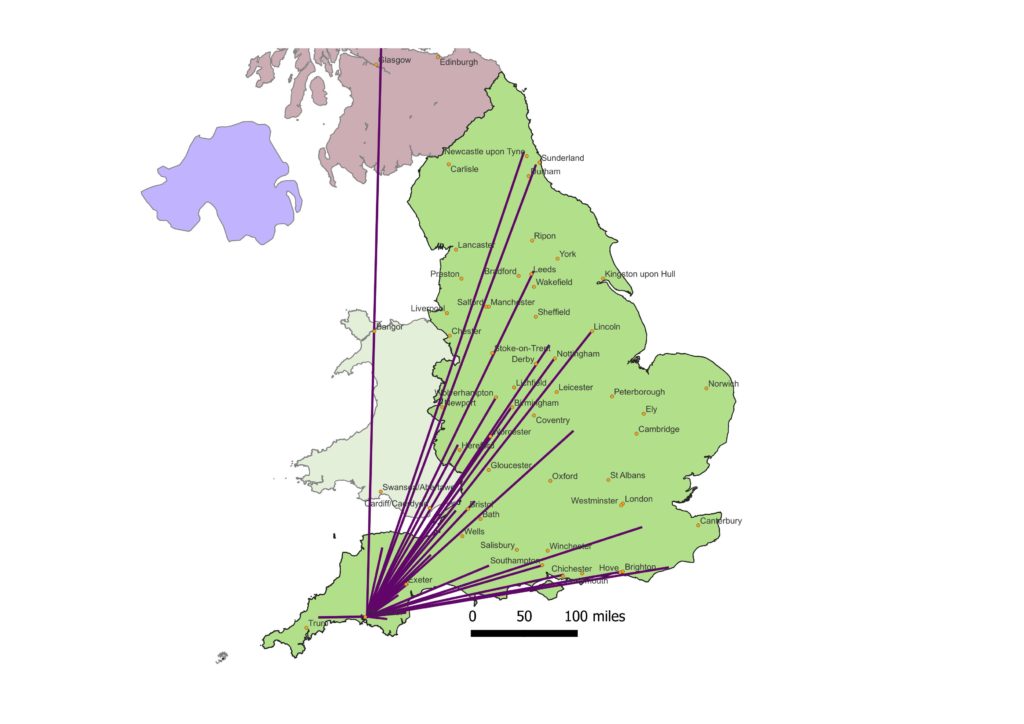

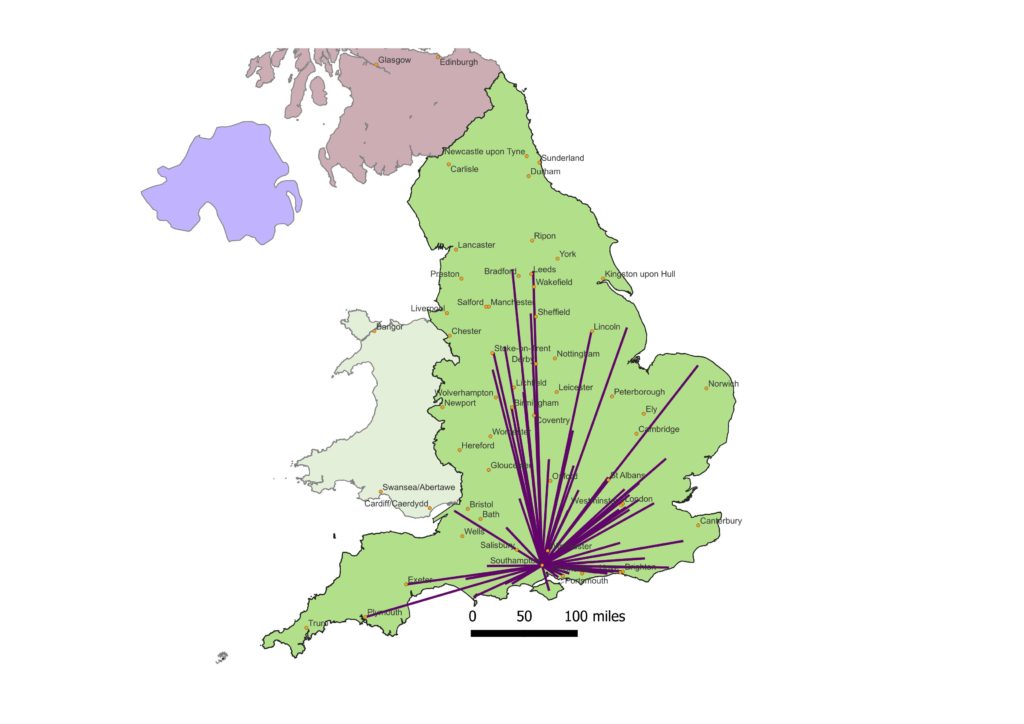

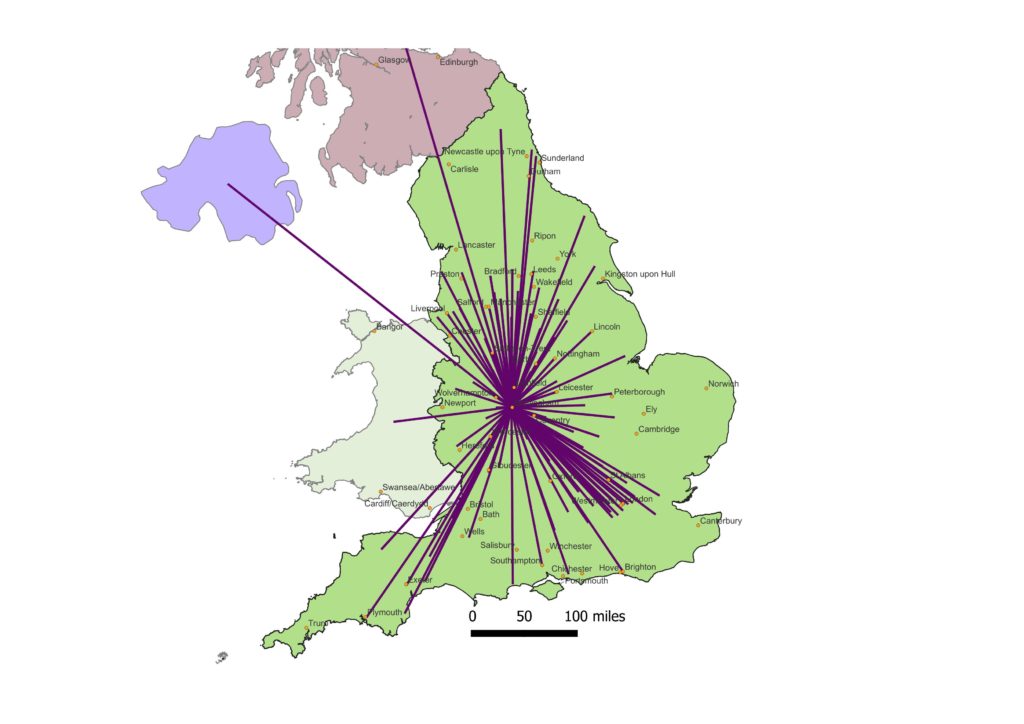

– to fail the tens of thousands of women and children who cross local authority boundaries to escape domestic violence and abuse.

As this research shows, the harms and losses caused by the perpetrator of domestic violence and abuse are often further compounded by how the state chooses to respond:

- the services it does/doesn’t provide

- the capacity and location of those services

- the eligibility for those services – which often focuses on location

Despite the evidence Government received on the domestic violence journeys across local authority boundaries, it chose to devolve the duties in Part 4 of the Act to provide services and safe accommodation to Tier 1 local authorities. It chose to create a mismatch between the scale of service responses, and the functional scale that women and children actually need – and deserve.

In a new podcast conversation, the problems and harms that follow from this are explored – including the cliff-edges created at local authority boundaries that women and children frequently fall off.

And the problems are rendered invisible at the national scale by the lack of data that crosses these boundaries. Both needs assessments and provision decisions are confined within local authorities, and the data that used to exist England-wide (and which is used in this Journeyscapes research) is no longer aggregated nationally and made available for research or to inform policy. It is a wilful ignorance of the impact of devolving service responsibilities to the wrong scale.

As the podcast highlights:

“the losses and the harms that are caused by the abuser in intimate partner violence, are being compounded by the losses and the harms which are caused by the state.”