After over a year of concern about the disruption to children’s schooling, it’s important to remember other issues that also affect children’s education – like their forced displacement due to domestic abuse[1].

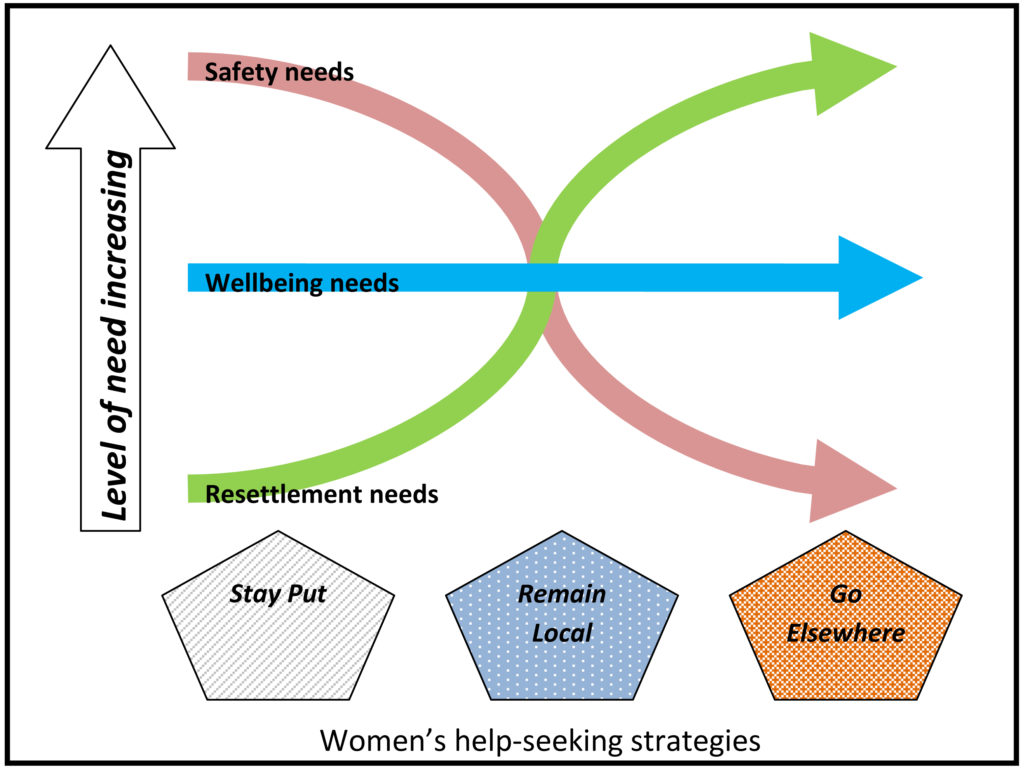

If mothers can seek help and support without having to relocate – by staying put – then children may be able to stay at school, and stay in contact with friends, teachers and other support to help them deal with their experiences of abuse. But this may not be possible.

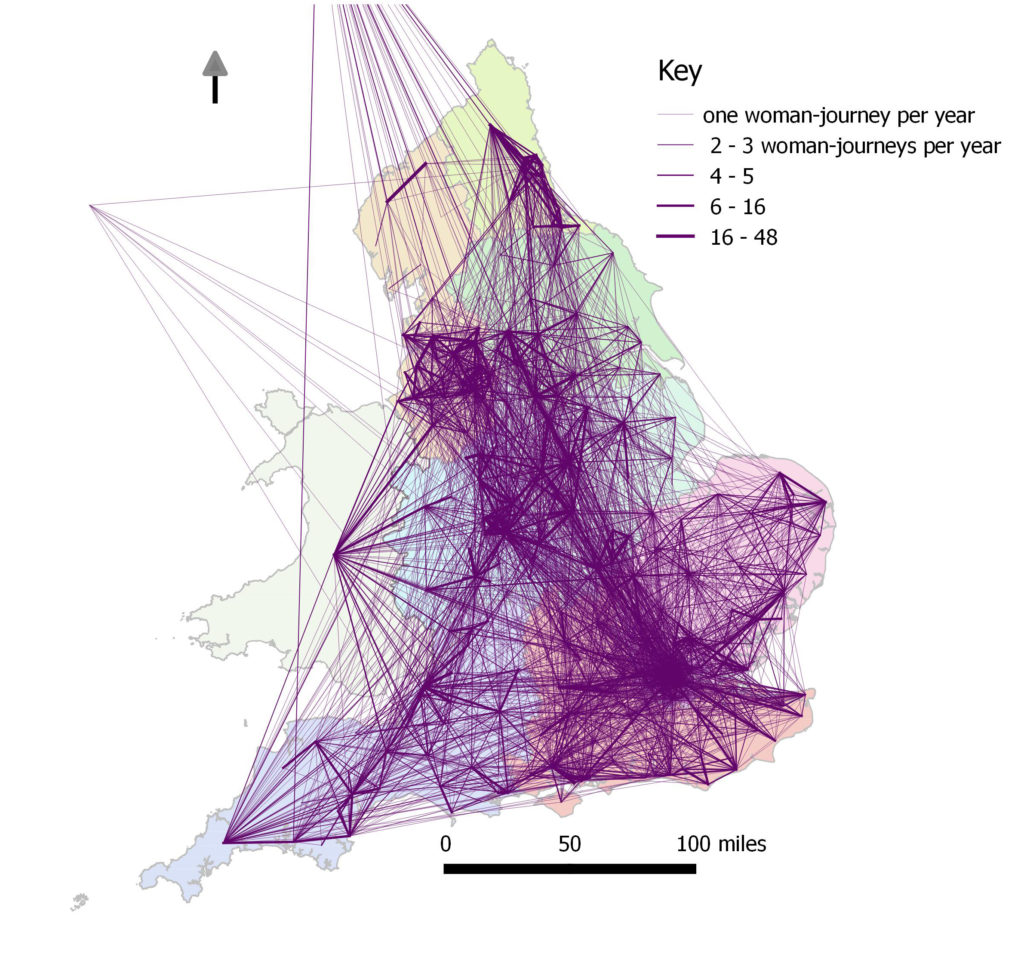

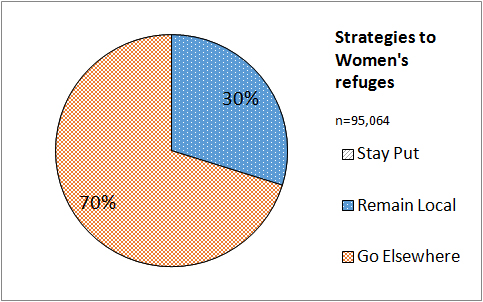

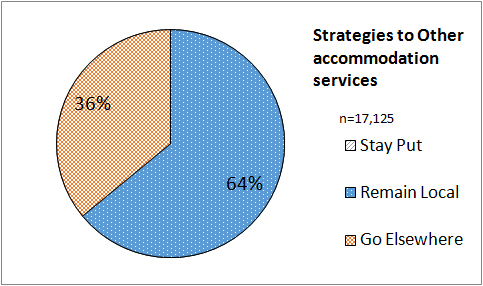

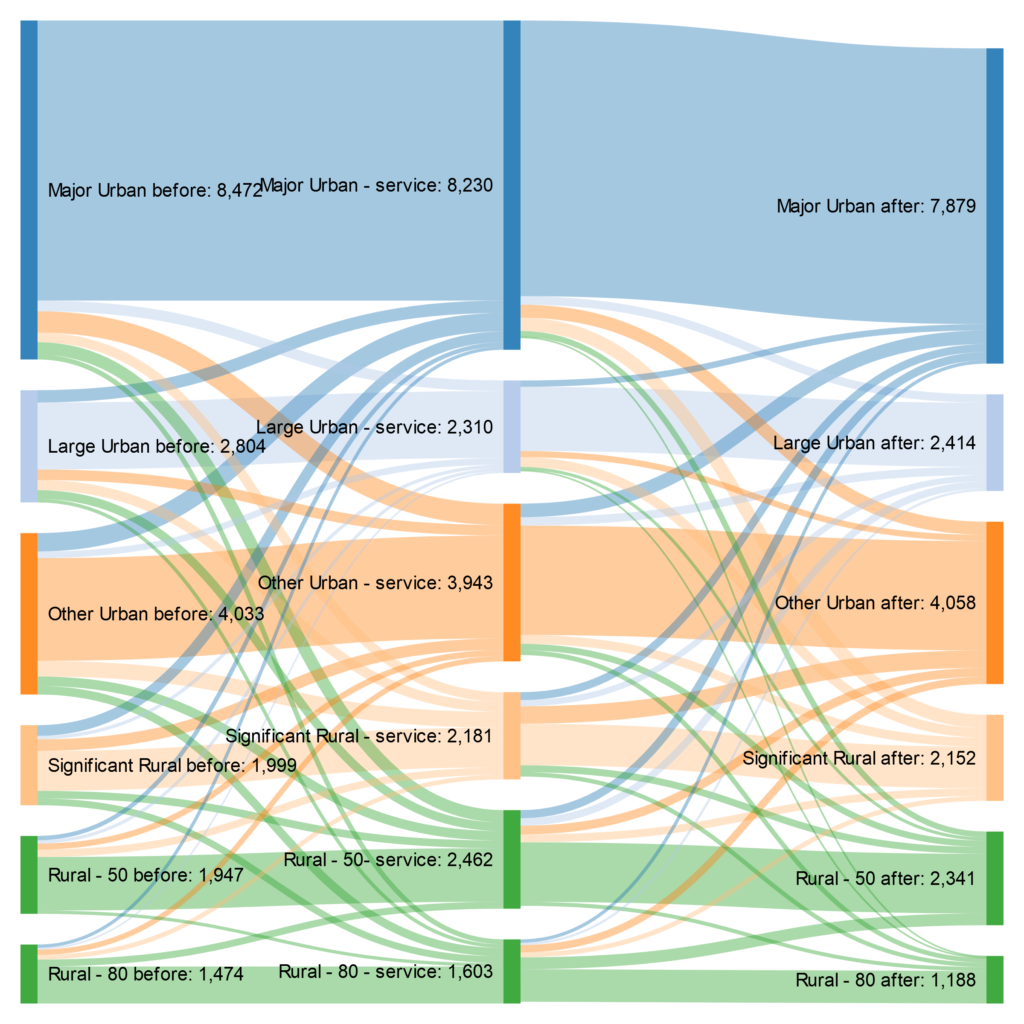

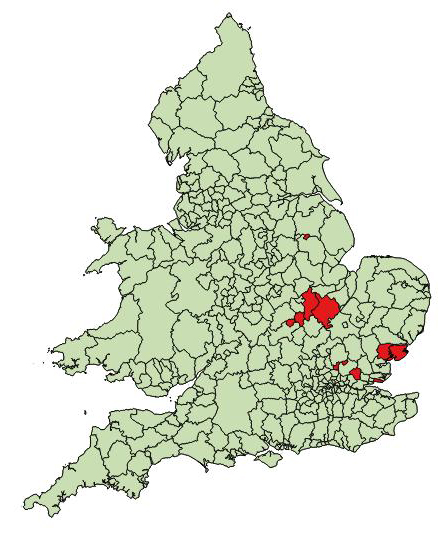

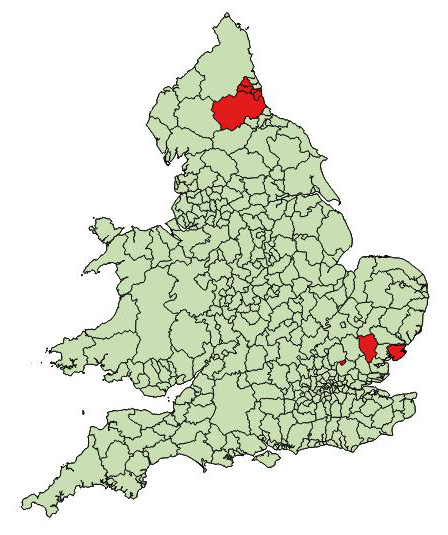

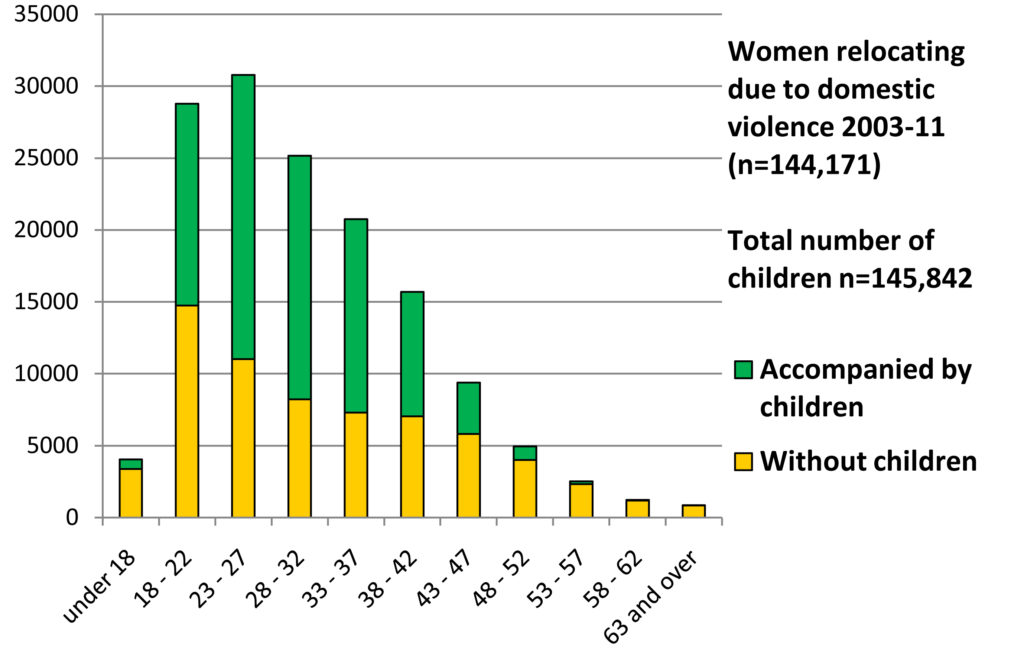

Around half of the women accessing services due to domestic violence have children with them, and over two-thirds are forced to relocate to seek help. Even if this is within the same local authority, children will often still have to change schools due to distance or safety concerns.

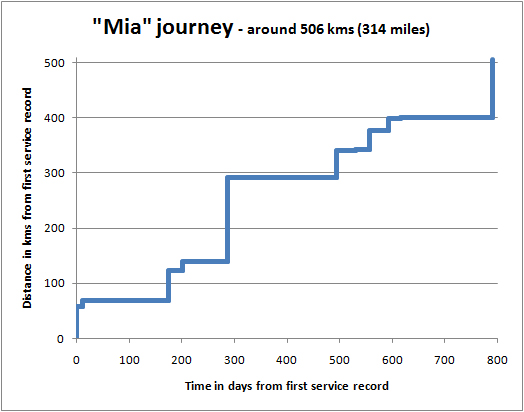

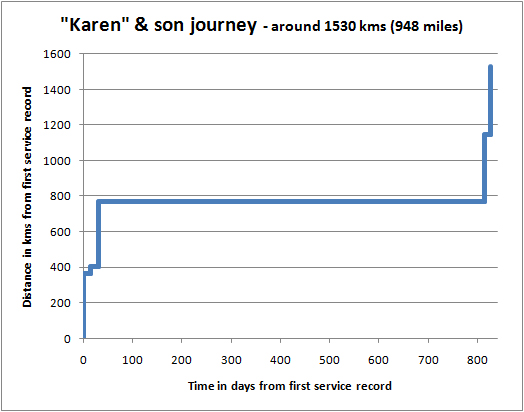

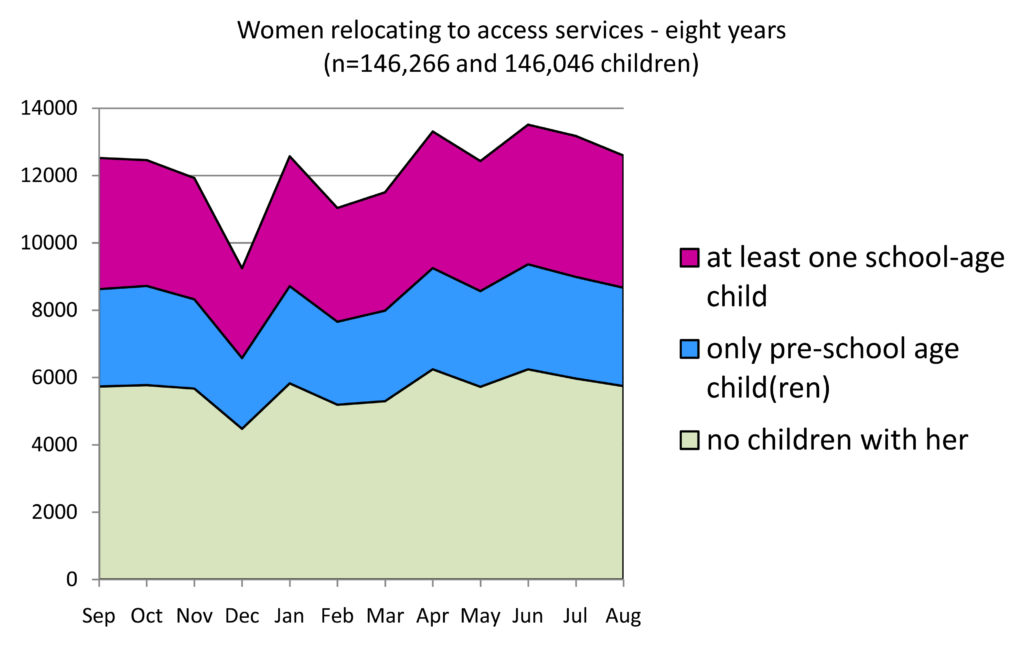

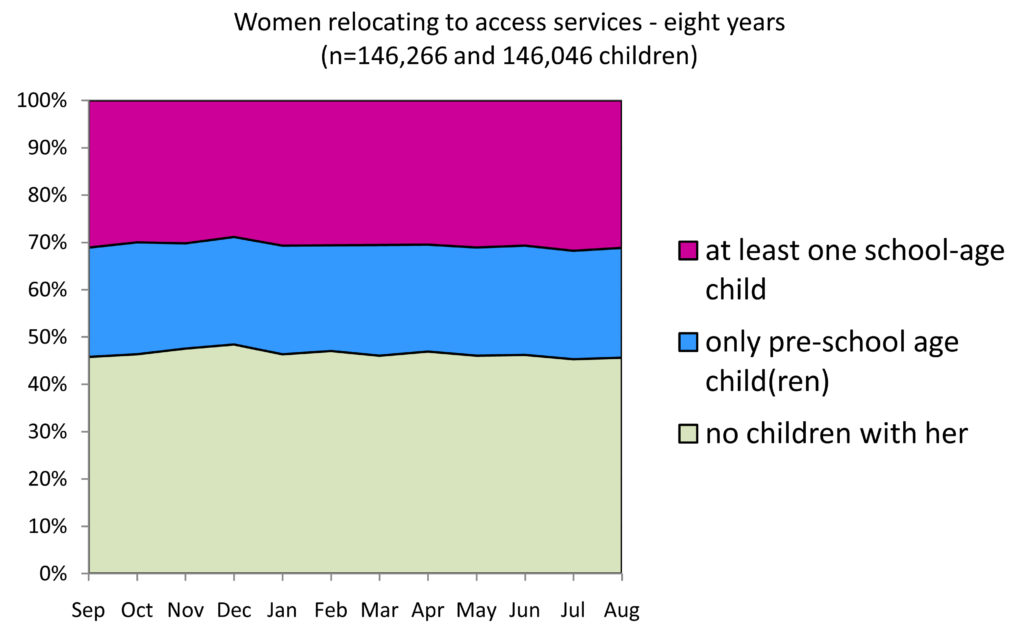

Though rates of help-seeking do vary somewhat during the year (see the graph below), with lower numbers in December, the patterns are very similar for women with and without children; and with school-age or pre-school children – as shown by the second graph below which shows the proportions through the year.

It’s clear that women often have very little choice about when and where they seek help – both because of the threat of the abuser, and the lack of service options. This includes the fact that many mothers of school-age children cannot avoid relocating during term-time, and children often face a further wait to get into a new school – and still longer to settle and begin to catch up.

Tracy talks about how the disruption to schooling has affected her son:

“It has all affected them so much; especially the older one – schoolwise. And the way I was – he was really affected emotionally as well – seeing me crying and unhappy, and all these changes, and coming to a new place from the old place.

For my son – changing schools – you know, it confuses children from one place to another. It’s like – he’s changed three times.”

Tracy & son (age 12), daughter (age 3)

Mothers have to seek help when and where they can – so it’s clear that it is vital to support children to resettle. They may be literally safe – especially if they go elsewhere – but needing support to get their lives back on track. This will include both the practicalities of getting back into school, but also the wider support to undo the harm of a disrupted education.

[1] This is based on a presentation at the forthcoming RGS-IBG Annual Conference: https://www.rgs.org/research/annual-international-conference/