Governments often find it easier to pass another law which claims to tackle a complex issue, rather than implement the laws that are already in place. And rather than develop and sustain the services and social infrastructure that are needed to make a real difference.

It looks like this is happening again in the UK. In February 2017 the UK Government – Theresa May herself – claimed “I believe that the plans I have announced today have the potential to completely transform the way we think about and tackle domestic violence and abuse”[1].

In March 2018 Theresa May pledged to “bring forward new legislation as part of my longstanding commitment to end domestic abuse”[2].

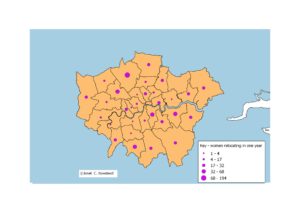

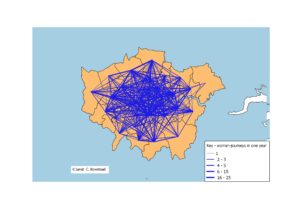

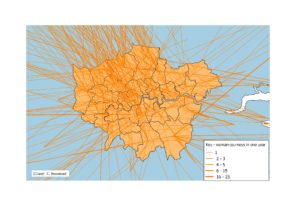

But the proposed Bill focuses yet again on the criminal justice system, with new definitions and the possibility of longer sentences for convicted perpetrators. It doesn’t focus on developing a society that prevents abuse and supports survivors. Many women who experience abuse go nowhere near the criminal justice system – often these are the tens of thousands of women (and children) who relocate every year in the UK.

If the Government wants to change the options and life chances of these women and children, it needs to ensure sustained funding for the specialist services all around the country that enable woman and children to rebuild their lives after abuse. We do not need a new law for that – we need everything from lessons on healthy relationships in schools, to refuges all around the country for women to escape to, to holistic and timely practical and emotional support.

This would need effective action[3] by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, by the Department for Education, by the Department of Health and Social Care, by the Department for Work and Pensions – not a new law.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/feb/17/theresa-may-domestic-violence-abuse-act-laws-consultation

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/08/theresa-may-domestic-violence-bill-women

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/oct/24/brexit-theresa-may-domestic-abuse-bill-universal-credit