Whilst the Government has made clear that anyone is allowed to leave home to “avoid or escape risk of injury or harm”[1], there is much else that is needed to make it possible for anyone to escape domestic abuse and get somewhere safe. Let alone the practicalities and support needed in the longer term.

Just thinking about the journeys of escape – the essential journeys – when women and children need to escape domestic abuse, how do they actually travel?

Because the journeys are very secret, not much has been known; but a new article has just been published from this research about different means of transport[2].

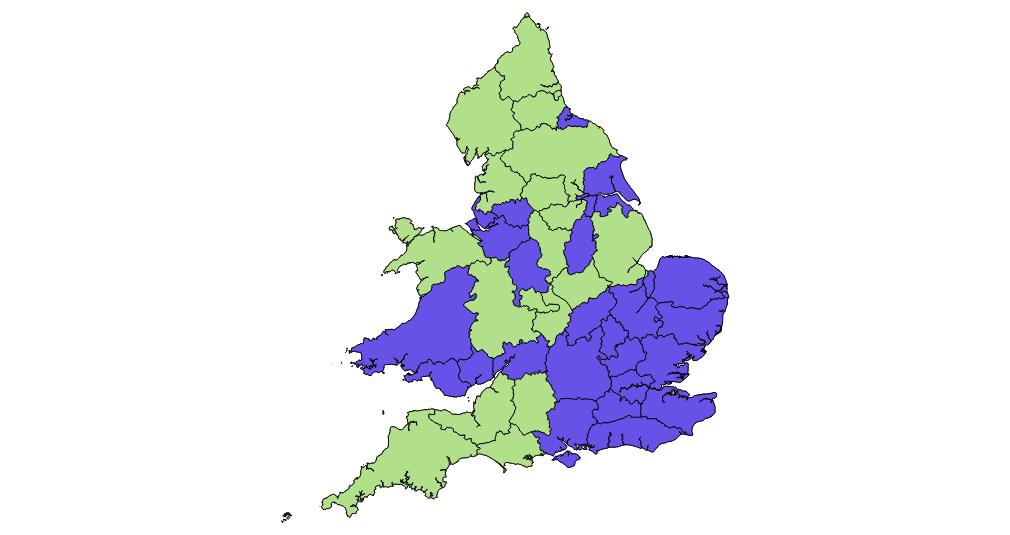

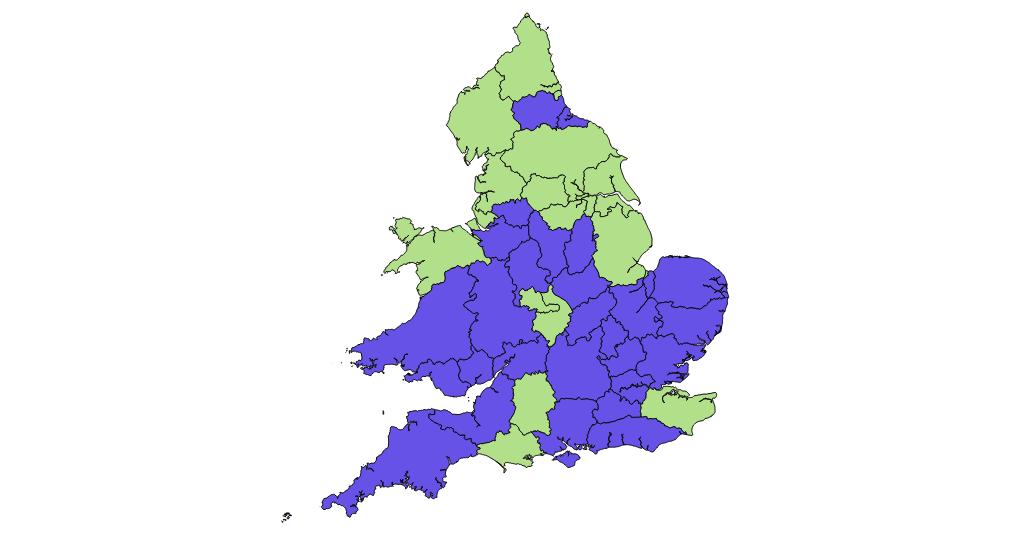

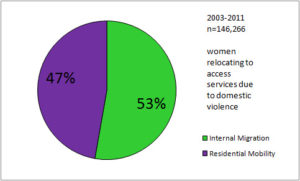

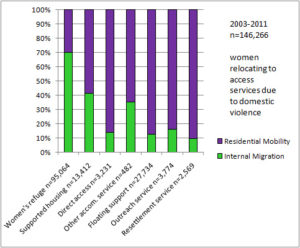

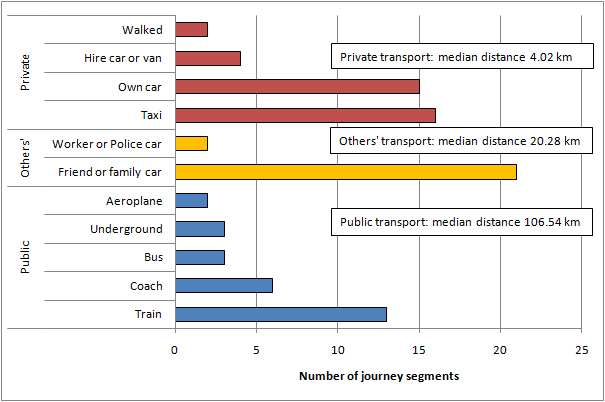

Public transport is extremely important – especially for longer distances – as the graph shows; however two-thirds of the journey stages were by private transport.

And, in the sample of women interviewed for this research, the largest category of transport was the private car of friends or family.

So – at this time – it is not just a problem of that initial escape due to:

- Increased surveillance from the abuser at home

- Risk of being questioned about how essential your journey is

- Difficulty accessing over-stretched support services and refuges

- Less public transport

It is also a problem that you cannot connect in the same way with others – friends and family – who could help you with both the actual journey, but also to plan how to make the journey safer and reduce the losses for you and your children.

This might be the initial essential journey away from an abusive partner; but it will also be all the further literal and emotional stages of your journey after that first step.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-outbreak-faqs-what-you-can-and-cant-do/coronavirus-outbreak-faqs-what-you-can-and-cant-do

[2] Bowstead Janet C. 2020. “Private violence/Private transport: the role of means of transport in women’s mobility to escape from domestic violence in England and Wales.” Mobilities, doi: 10.1080/17450101.2020.1750289 Available here: Private violence/Private transport: the role of means of transport in women’s mobility to escape from domestic violence in England and Wales